Updating Toyota’s 1KZ‑TE Oil Recommendations for 2026: Part 1.5 The Nerdy Oil Stuff

Inside Diesel Engine Oil: Base Stocks, Additives, and Viscosity

In Part 1 of our 1KZ-TE engine oil series, we focused on practical oil recommendations (viscosity grades, change intervals, API ratings) for Toyota’s 1KZ-TE 3.0L turbodiesel. Now, as a Part 1.5, we’ll dive deeper for the technically minded readers who want to understand why certain oils are recommended. This companion article cuts through marketing language and explores what’s actually inside engine oil – from the base stock categories (Group I–V) to the complex additive packages – with an emphasis on diesel applications and older engines like the 1KZ-TE. We’ll explain how different base oil types affect performance, how key additives (like ZDDP, detergents, dispersants, etc.) work to protect a diesel engine, what viscosity grades and viscosity index really mean, and debunk a few common oil myths. Along the way we’ll reference tribology research, industry standards (API, SAE, ASTM), and real testing data to back up the discussion. By the end, you’ll have a clearer, evidence-based understanding of what makes a high-performing diesel engine oil – and why our Part 1 recommendations make sense for your 1KZ.

Base Oil Groups I–V: The Foundation of Lubricants

Every motor oil starts with a base oil, typically making up ~75–90% of the final product (the rest is additives)[1][2]. The American Petroleum Institute (API) classifies base oils into five groups (I through V) based on how they’re made and their chemical properties[3][4]. Here’s a quick overview:

Group I – Solvent-refined mineral oil. These are the “traditional” base oils from older refining tech. Group I oils contain less than 90% saturates (more reactive hydrocarbons), more than 0.03% sulfur, and have a viscosity index (VI) of 80–120[5]. They tend to be amber-colored (due to sulfur/aromatics) and have relatively lower stability. Group I was common for decades, but its use is declining as performance demands rise[6][7]. It’s generally the cheapest base stock.

Group II – Hydrotreated mineral oil. Group II is more refined: >90% saturates, <0.03% sulfur, VI 80–120 (similar VI range as Group I, but far purer)[8]. Making Group II involves hydrogen gas treatment (hydrocracking) to remove impurities (sulfur, nitrogen, ring aromatics) more thoroughly[9][10]. The result is a clear, colorless oil with better oxidation stability than Group I[10]. Group II has largely overtaken Group I for modern engine oils – it’s still considered “conventional” mineral oil, but high-quality. In fact, Group II base oils are now extremely common in automotive engine oil formulations[11], including many diesel oils, because they hit a sweet spot of performance and cost. (There’s also “Group II+” sometimes mentioned, an unofficial term for Group II with VI ~115)[12].

Group III – Ultra-refined mineral oil, sometimes marketed as “synthetic.” Group III oils are also derived from crude but undergo severe hydrocracking/hydroisomerization at even higher pressure/temperature to yield an even purer product[13][14]. They have >90% saturates, <0.03% sulfur like Group II, but VI > 120[13]. In plain terms, Group III has a higher viscosity index – it thins out less at high temps. Although Group III comes from petroleum, the intensive processing actually changes the molecular structure so much that many companies call it “synthetic” (especially for marketing in North America)[14]. Group III base oils are clear, very stable, and often used in premium oils or lower-viscosity multigrades. They cost more than Group II but are cheaper than true synthetics. Many “full synthetic” diesel engine oils on store shelves today are actually Group III-based.

Group IV – Polyalphaolefins (PAO), which are true synthetic hydrocarbons. Group IV oils are manufactured in a chemical plant by polymerizing olefin molecules, rather than by refining crude[15]. PAOs have very uniform molecular structures, resulting in excellent properties: high viscosity index (typically >130), outstanding cold-flow (pour points) and thermal stability[16][17]. They remain fluid at extreme cold and stable at high heat – great for severe conditions. PAO synthetics have been around ~50 years and are a common base for top-tier engine oils. They are more expensive to produce than Group III[18]. Often, oils labeled “PAO synthetic” or meeting very demanding specs will use Group IV. For example, a 0W-40 or 5W-40 that stays stable in a turbocharged diesel’s high temperatures might use some PAO to ensure it meets performance requirements.

Group V – All other base oils not in I–IV. This is a catch-all for specialty stocks: esters, polyalkylene glycol (PAG), phosphate esters, silicones, biobased oils, naphthenic oils, etc.[19]. Group V oils are usually not used alone as the main base fluid (with some exceptions) but are blended in to impart specific benefits. For instance, esters (common Group V components) are often added to PAO formulations because esters have natural detergency and can handle very high temperatures – they help keep engines clean and stable under heat[20][21]. Esters also have polar molecules that can improve oil’s seal conditioning and solubilize additive packages. In diesel oils, a small percentage of an ester Group V can boost the overall performance of a Group III/IV base. Group V also includes older-style naphthenic oils used in some niche applications. Think of Group V as the “special sauce” to tweak properties of the base stock blend[20].

It’s common for a finished engine oil to use a mixture of base stocks. For example, a 15W-40 diesel oil might use mostly Group II, plus a bit of Group I for additive solubility, or a dash of Group V ester for improved detergency. A synthetic 5W-40 could be primarily Group III with some Group IV PAO and Group V ester to fine-tune cold flow and volatility. The base oil mix is chosen based on the performance needed (cold start, high-temp viscosity stability, volatility, etc.) and cost constraints[22][23]. Over the years, the trend is toward higher group oils as industry specs tighten – one survey found that in modern lubricant plants Group II now accounts for ~47% of capacity vs ~28% for Group I (Group I use has roughly halved from a decade prior)[24][7]. In heavy-duty diesel oils today, Group II and III are workhorses, with Group IV/V reserved for top-tier synthetic products.

What’s In Diesel Oil Additives? (ZDDP, Detergents, Dispersants & More)

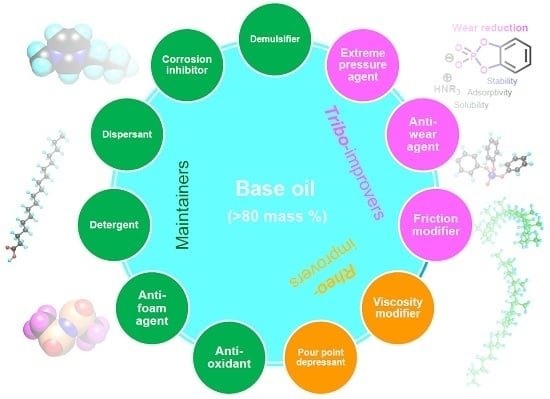

While base oil quality is critical, it’s the additive package that truly differentiates one engine oil from another. In fact, many oils share similar base oils – it’s the additives that make an “engine oil” versus an “ATF” versus a “gear oil.” We’ll explore that more later. For now, let’s examine the key additives in diesel engine oil and how they work. Heavy-duty diesel oils typically contain a robust additive package, often 15–25% of the oil’s volume (higher than the ~10–20% in passenger car oils)[2][25]. These additives perform a range of functions that are especially important in diesel engines:

Antioxidants – Combat oil oxidation (reaction with oxygen at high temps). Oxidation causes acids, sludge, varnish, and viscosity increase. Antioxidant additives (typically zinc or calcium sulfonate, hindered phenols or aromatic amines) slow the oxidation process, keeping the oil from thickening or forming deposits during long, hot operation[26]. This is vital in diesel engines that run hotter and often have longer drain intervals than gasoline engines.

Anti-wear additives – Prevent metal-to-metal contact under high load by forming a protective sacrificial film on component surfaces[27]. The most famous is ZDDP (zinc dialkyldithiophosphate), used since the 1940s. ZDDP is exceptionally effective: under heat and pressure it reacts to form a thin phosphate glass layer on rubbing surfaces, which takes the wear instead of the underlying steel[28]. This tribofilm reduces scuffing and cam/tappet wear and even provides some antioxidant benefit[28]. Diesel oils historically have used generous ZDDP doses to protect tough parts like cam lobes, lifters, and injector pump gears. (We’ll revisit myths about ZDDP later – more isn’t always better!). Modern formulas may also include ashless anti-wear or friction modifiers like molybdenum compounds (e.g. MoDTC), which supplement ZDDP and can further reduce friction. But ZDDP remains the primary anti-wear agent in most engine oils, diesel and gasoline alike[29].

Dispersants – Keep insoluble contaminants suspended in the oil. Diesel combustion produces soot – essentially microscopic carbon particles – that blow into the oil. If not controlled, soot will clump into sludge, increase viscosity, and abrade engine parts. Dispersant additives are polar molecules that attach to soot and keep particles from agglomerating[30]. They act like microscopic detergents that don’t ash when burned (thus called “ashless” dispersants, typically polyisobutylene succinimides). Dispersants are absolutely critical in diesel oils because diesel engines produce 10–100× more soot than gasoline engines, with soot levels reaching 3–6% by weight in the oil during normal service[31][32]. Without strong dispersants, a diesel oil would sludge up quickly. In fact, handling soot is a defining requirement of diesel oil additives: one technical source notes diesel additive packages contain 2–3× the dispersant level of gasoline oils[33][34]. Dispersants keep soot finely distributed so it can harmlessly circulate until your oil change. (They also help with other contaminants like oxidized oil particles.)

Detergents – Chemical cleaners that prevent deposits and neutralize acids. They typically are metallic soaps, e.g. overbased calcium sulfonate or calcium phenate, sometimes magnesium compounds[35][36]. Detergents have two jobs: 1) scrub away and prevent high-temperature deposits (like piston ring area varnish or turbo coking) and 2) provide alkaline reserve (TBN) to neutralize acidic byproducts (sulfur and nitrogen acids from combustion). Diesel engines, even with modern low-sulfur fuel, generate more acid and soot blow-by than gasoline engines, so they demand higher detergent/TBN. Typical Total Base Number for diesel oils is 10–15 mg KOH/g, versus ~6–8 for gasoline oils[37][38]. That means diesel oils carry more neutralizing power to handle acids over long drains. Calcium sulfonate is common in heavy-duty oils because it’s very effective at neutralizing sulfur acids and also lays down protective films at hot spots (it even can provide some anti-wear film in tribological interactions)[39][40]. These detergents do contribute to ash when burned (the metallic components don’t fully combust), which is fine in older engines but must be limited in engines with particulate filters (DPF) – more on that shortly. Detergents are “consumed” over the oil’s life as they neutralize acids, hence one monitors TBN depletion to judge oil life[41].

Pour-point depressants – Additives that improve low-temperature flow by preventing wax crystal formation[42]. Mineral base oils contain waxy molecules that can solidify in the cold. Pour-point depressants (PPDs) are polymers that interfere with wax crystal growth, keeping oil fluid at low temps. These are important for cold-cranking ability, especially in conventional 15W-40 oils used in winter. They’re less critical in synthetics (which inherently have low pour points), but most multigrade oils have some PPD to meet cold pumpability specs.

Viscosity Index Improvers (VII) – Long-chain polymer additives that reduce how much the oil thins out at high temperatures[43]. VI improvers have relatively little effect at low temperature (they coil up), but as temperature rises they expand and increase the oil’s viscosity, thereby bolstering the oil’s thickness at 100°C+. This is how an oil can achieve two SAE grades (e.g. 15W-40): a lighter base oil is blended with polymers that make it behave like a thicker oil when hot. VII polymers are what make an oil “multi-grade.” Without them, an SAE 40 monograde would be very thick when cold and then quite thin at operating temp – too wide a swing. By adding VIIs, a 15W-40 can be relatively thin at cold crank (15W spec) yet not overly thin at 100°C (acts like a 40). The caveat is these polymer molecules can shear under high stress, permanently reducing viscosity. Diesel engines, especially, can be brutal on VI improvers (high-pressure injectors, cam and gear drives can cut up the polymer chains). Good heavy-duty oils therefore use highly shear-stable VIIs, and industry tests like the Kurt Orbahn shear test ensure oils stay in grade. (For example, Infineum recently developed new diblock copolymer VI modifiers to improve heavy-duty oil shear stability and soot-handling[44][45].) We’ll discuss viscosity index in more detail later, but it’s worth noting here that the base oil’s native VI also matters – e.g. a Group III or PAO has a high VI, needing fewer VII additives to achieve a multigrade span. Fewer VIIs generally means an oil is more resistant to shear and high-temperature deposits. This is one reason synthetic-base oils (Group III/IV) are prized for wide-range multigrades.

Anti-foam agents – Typically silicone polymers added in tiny doses (<0.1%) to collapse air bubbles and foam in the oil[46]. Diesel engines (especially large turbo diesels or those in off-road equipment) can churn the oil significantly, entraining air. Foam in oil is dangerous because it disrupts the oil film and accelerates oxidation. The anti-foam additive reduces surface tension of bubbles, causing them to burst. It’s a small but important part of the additive package – especially for engines that see rough service (4x4 vehicles, heavy equipment on inclines, etc., where sloshing can foam the sump). Without anti-foam, aeration could lead to lifter noise, low oil pressure, or even bearing damage, so this additive quietly does important work[46].

In addition to the above, there are often corrosion inhibitors to protect bearing surfaces during downtime, and metal deactivators if yellow metals (copper/bronze) are in the system (to prevent additive reactions with them). The additive package is truly a carefully balanced chemical stew. In fact, there can be antagonism or synergy between additives – for instance, dispersants can compete with ZDDP for surface area, potentially reducing ZDDP’s film strength if not formulated correctly[47]. Additive manufacturers spend huge R&D effort to get these chemistries balanced so that, for example, you have enough detergency for long drains but not so much that the oil becomes too ash-rich and risks deposits.

A key difference in diesel vs. gasoline oil additives is the SAPS content – sulfated ash, phosphorus, sulfur – mostly coming from metallic detergents and ZDDP. Modern diesel engines with aftertreatment devices (DPFs, SCR catalysts) require low-SAPS oils to avoid poisoning catalysts or clogging DPFs with ash. Specs like API CJ-4/CK-4 and ACEA E6/E9 limit the ash % and phosphorus in oil (typically ≤1.0% ash, ≤0.08% P). This forced formulators to use lower metal detergent and ZDDP levels and compensate with other technologies (e.g. ashless antioxidants, dispersants, and alternative anti-wear agents)[48][49]. For older engines like the 1KZ-TE (which has no DPF and originally spec’d API CF-4 or CF oil[50]), a higher-SAPS oil (with plenty of calcium and zinc) is acceptable and often beneficial for its cleaning and anti-wear reserve. Those engines were designed in an era of higher-ZDDP, higher-ash oils. However, they can also run fine on a modern low-SAPS oil — as long as it meets at least the older API performance category (e.g. API CK-4 covers and exceeds all the wear/cleanliness requirements of API CF-4). In fact, field and lab tests have shown no increase in wear metals when phosphorus levels were reduced in newer oils, because additive tech has improved to compensate[51][52]. We’ll revisit this in the myth section, but it’s fascinating that an older diesel doesn’t necessarily “need” the extremely high ZDDP of yesteryear if the oil is well-formulated with ashless anti-wear boosters.

To summarize this section: diesel engine oils are formulated with a very robust additive package to handle the high soot, high temperatures, and acid blow-by of diesel engines. They contain more detergents and dispersants than gasoline oils (to manage soot and deposits)[33][53], and traditionally more ZDDP for wear protection[54] (though moderated in newer low-ash oils). They also prioritize oxidation stability for long drains at high loads[55][56]. These additives are what allow a diesel oil to keep an older engine like the 1KZ-TE clean internally and protected over thousands of kilometers. If you’ve ever opened up a high-mileage diesel that’s been fed a good oil and found clean metal and minimal sludge, you can thank the detergent-dispersant package and antioxidants working in concert. In contrast, using an oil not rated for diesel (say a generic gasoline oil in a diesel) can lead to rapid sludge and wear because it might lack the needed TBN or dispersants – a risk not worth taking. Always use oil with the appropriate API diesel rating for your engine (e.g. CH-4, CI-4, CJ-4, etc.), because that assures the additive package is up to the task.

Base Oils vs. Additives: Why Oil Type Depends on Additives

It’s often said that the additive package defines the oil’s application, and base oils can be quite interchangeable across products. This is true to a large extent. Many lubricants – engine oils, ATFs, gear oils, hydraulic oils – might start from similar or even the same base stock (say a Group III oil of 6 cSt @100°C). What makes them totally different products is the additives blended into that base. Oil companies often source base oils from the same few refineries; for example, ExxonMobil and Shell are two of the world’s major producers of high-quality base stocks, and many boutique oil brands simply buy those base oils and add their proprietary additive package to create the final product[57]. So, brand X’s “synthetic” and brand Y’s “synthetic” might be built on the exact same Group III base oil, with different additive chemistry differentiating them[57].

Let’s consider an example: Automatic Transmission Fluid (ATF) vs Engine Oil. Both are lubricants that might use a mix of Group II/III base oils. Viscosity-wise, ATF is roughly equivalent to an SAE 20 grade engine oil (about 7 cSt @100°C, similar to a 5W-20)[58]. The base oil types used can overlap – indeed, ATFs and motor oils commonly use Group II, III, or IV base oils depending on the performance level and cost[59]. The big difference is in the additives: ATFs contain specialized friction modifiers for the transmission’s clutch packs, extreme pressure agents for gear sets, and typically no dispersants or high TBN detergents (since ATF doesn’t deal with combustion soot or acids). Engine oil, on the other hand, has lots of detergents/dispersants and anti-wear like ZDDP, but relatively minimal friction modifier (you actually don’t want too slippery an oil for an automatic transmission, where controlled friction is needed for clutch engagement). As a transmission expert magazine put it: “There is much ATF and engine oils have in common, until you get to the additive package. Each application requires a proper additive package to meet its specific frictional and protection requirements.”[60] In fact, all three types of modern AT (step-AT, CVT, DCT) may use similar base oil blends (Group I-IV) and viscosity, but each demands a unique additive system tuned for that transmission’s needs[61][62].

Another example: Gear oil vs Engine oil. An 80W-90 gear oil and a 15W-40 engine oil have comparable kinematic viscosity (~14 cSt at 100°C). One could be formulated from the same base stocks as the other. But the gear oil will contain heavy-duty extreme-pressure (EP) additives (sulfur-phosphorus compounds that form a protective film under the high tooth pressures in a differential or gearbox) – these EP additives have a distinct odor and would be harmful in an engine (they can attack yellow metals and create deposits in combustion). Conversely, the engine oil’s high level of dispersants and detergents would be mostly unnecessary in a closed gearbox (and could actually affect friction or foaming). So, use the right oil for the application – not because the base oil is mysteriously different, but because the additive chemistry is optimized for each use-case. As one Mobil engineer remarked in a Q&A, all motor oils start with base oil and then “it’s the additives” that differentiate performance[57].

For those curious, this is why you’ll see some multi-purpose oils on the market (e.g. universal tractor fluids that claim to lube engine, transmission, and hydraulic systems). Such oils make careful compromises in additive levels to meet minimum needs of each system. However, a dedicated oil will typically perform better in its specific domain because it doesn’t compromise. Never assume two oils with similar base stocks are interchangeable if their additive packages are different – e.g., don’t run ATF in your engine just because it “feels like a thin oil”; it lacks critical anti-wear and detergency additives needed for engines and can lead to rapid wear. Likewise, using a diesel engine oil in a gasoline car is usually okay (diesel oils often carry dual ratings), but using a gasoline-only oil (API SP) in a diesel can spell trouble, as it might not handle the soot or acid (unless it also meets diesel specs).

From a manufacturing standpoint, it’s efficient: refineries produce large batches of high-quality Group II/III base oils, and lubricant blenders create different products by adding different additive packages to that base. So indeed, the base oils across ATF, engine oil, hydraulic oil can be chemically similar or even identical – it’s the additive soup that truly defines the fluid. A great real-world illustration: Porsche (and other automakers) often have a list of approved engine oils. Mobil 1 might be factory fill. But some enthusiasts think another brand with more ZDDP etc. is “better.” Mobil’s engineers pointed out that many boutique oils use the same base stock, just a different additive cocktail[57]. The performance differences in normal use are negligible as long as both meet the required spec[51][63].

In short, oil is a functional fluid engineered for a purpose. The best way to ensure you’re using the right thing is to follow the specs (API, ACEA, manufacturer approvals) – those specs are essentially shorthand for “has the right additive package and performance for this application.” That matters far more than marketing terms like “synthetic” or fancy base oil claims. Even a high-end Group IV base oil will fail in service if the additive pack is wrong for the job.

Making Sense of Viscosity Grades and Viscosity Index

Viscosity is arguably the most important property of a lubricant – it’s literally the “thickness” or resistance to flow that keeps metal surfaces separated. But oil viscosity isn’t one fixed value; it changes with temperature (thinning when hot, thickening when cold). The SAE viscosity grade on your oil (e.g. 5W-40, 15W-40) is a classification to standardize how an oil behaves at cold and hot temperatures. The Society of Automotive Engineers SAE J300 standard defines these grades with specific test criteria. In brief, for a multi-grade oil like 15W-40:

The first number (with a “W”) relates to low-temperature performance (W = winter). A 15W rating means the oil meets maximum viscosity limits at cold cranking and pumping tests (for 15W, roughly: cranking < 7000 cP at –20°C, pumping < 60,000 cP at –25°C, per J300 specs). A 5W oil, by contrast, has to stay fluid at much lower temperature (tested at –30°C, etc.)[64][65]. In practice, the lower the “W” number, the better the oil flows when your engine is cold.

The second number (the “operating” viscosity grade) is defined by the oil’s kinematic viscosity at 100°C, plus a minimum high-temperature high-shear viscosity at 150°C. For example, an SAE 40 grade oil must measure between 12.5 and 16.3 cSt (mm²/s) at 100°C, and have HTHS (High-Temp High-Shear) viscosity ≥ 3.5 mPa·s at 150°C. An SAE 30 by comparison is ~9.3–12.5 cSt at 100°C (HTHS ≥ 2.9). These ensure the oil isn’t too thin to protect a hot engine. The multigrade oil meets requirements for both a low-temp “W” grade and a high-temp grade[66][67]. For instance, 5W-40 satisfies 5W cold cranking specs and falls in the 40-grade range at 100°C.

The Viscosity Index (VI) is a number that indicates how much an oil’s viscosity changes with temperature. High VI means the oil’s viscosity is more stable across temps (it doesn’t thin out as rapidly when heated)[68]. Low VI means it’s very sensitive to temp changes (like older pure mineral oils that turn to molasses in the cold and water when hot). Most conventional oils have VI around 95–105, while synthetics can have VI of 130–150 or even higher[69][70]. For example, water has an extremely high VI (it barely changes viscosity with temp), whereas honey has a low VI (huge difference between cold and warm). You want your engine oil to behave more like water in that sense – thin enough when cold to flow, but not too thin when hot. Viscosity Index Improver additives, as discussed earlier, are used to raise the VI of the finished oil, creating a flatter viscosity-vs-temperature curve.

Viscosity vs. temperature for an SAE 40 monograde oil (yellow) compared to a 5W-40 multigrade synthetic (red). Note that the 5W-40 is much less viscous at cold temperatures, enabling easier cranking and faster lubrication at startup, yet at operating temperatures (~80–100°C) it maintains similar or higher viscosity than the straight 40 oil. In contrast, the monograde 40 is extremely thick at low temps and actually becomes thinner than the 5W-40 at high temps due to its lower viscosity index[71].

The above graph and description illustrate why multigrade oils are so beneficial. In a 1KZ-TE turbo diesel, for instance, Toyota manual recommends 5W-30 as the preferred oil for most conditions, explicitly citing “better fuel economy and good starting in cold weather.”[50]. A 5W-30 or 5W-40 has superior flow at startup – important because a huge proportion of engine wear occurs in the first seconds after a cold start when oil is still reaching all the components. By flowing faster, a 5W-XX reduces those metal-on-metal moments. A heavier 15W-40, by comparison, might be fine when the engine is hot, but on a freezing morning it can be nearly three times more viscous during cranking than a 5W-40[71]. That can mean slow cranking, delayed oil pressure, and possibly valve train clatter until the oil circulates.

On the flip side, viscosity at operating temperature affects the oil film thickness under load. If viscosity is too low for the engine design, the oil film can become too thin to prevent contact, especially in bearings or cam followers under high stress. That’s why you shouldn’t run an xW-20 in an engine designed for xW-40 – at 120°C oil temps under heavy load, a 20-grade’s film may not carry the load, leading to wear or metal fatigue. Diesel engines in particular often require higher HTHS viscosity for bearing protection under sustained load (e.g. towing). The 1KZ-TE, being an older design, was spec’d for xW-30 or xW-40 oils[50], indicating it expects an HTHS around 3.5 or above. Modern light-duty diesels and gasoline engines sometimes spec lower viscosities (0W-20, 5W-30) if they’re engineered for it (tight bearing clearances, lower shear stress, and in pursuit of fuel economy). But even so, those oils must prove themselves in industry wear tests to get the spec approvals.

High Viscosity Index base oils (like Group III/IV) have another advantage: they inherently give you a wide temperature performance with less reliance on polymer VIIs. For example, an oil formulated largely with a PAO base might achieve 5W-40 with minimal VII additive. Fewer VIIs means the oil is more shear-stable (since there are fewer large polymer molecules to chop up). This is why many synthetic diesel oils are offered in grades like 5W-40 or 0W-40 – the base stock can handle the span. On the contrary, achieving a 5W-40 with cheaper Group I/II stocks would require a lot of polymer, which might shear out of grade after hard use, effectively turning your 5W-40 into a 5W-30 over time. This has been observed in some fleet usage – oils formulated with better base oils tend to stay in grade longer. Field tests (e.g. Infineum’s trials) show that modern polymers and base stocks can keep even a 15W-40’s viscosity “within grade” out to 35,000 miles in a diesel truck, whereas older formulations might have sheared significantly by then[45][72]. The takeaway: viscosity retention is an important performance metric, and it’s a function of both base oil choice and the shear-stability of VI improvers.

It’s also worth noting that oil viscosity can change in service not just by shearing down, but also by thickening due to contamination. For example, soot loading in diesel oil will steadily raise the viscosity (soot particles make the oil behave thicker)[73][74]. Oils are formulated to tolerate a certain soot percentage – up to ~4-6% in heavy-duty tests – before viscosity blows out of spec[75]. That’s why API CK-4 oils have to pass tests like the Mack T-11, which measures viscosity increase with soot. Good dispersants keep the soot fine and the viscosity rise gradual; poor soot control could cause the oil to gel or thicken rapidly. Fuel dilution is another factor: any diesel that does a lot of idling or short runs may accumulate diesel fuel in the oil, which lowers viscosity (fuel thins the oil). If you see an oil analysis where viscosity dropped, fuel dilution is often the cause. So viscosity in your engine isn’t static – it’s dynamic, influenced by VI, additives, and what the engine throws at the oil (soot, fuel, heat). This is why oil analysis labs like Blackstone emphasize investigating any viscosity that comes back out of the expected range[76][77].

In summary, follow your engine’s viscosity recommendations (they are based on extensive testing). For the 1KZ-TE, Toyota’s manual favored 5W-30 for general use[50], but allowed up to 15W-40 or 20W-50 in hotter climates (see the temperature chart in the manual)[78][79]. Using a lighter viscosity than specified can risk wear under load; using a heavier viscosity than needed can hurt cold start lubrication and even running temperature. Optimal viscosity is about balance. In fact, running too thick an oil can elevate oil temperature and reduce engine efficiency because the engine expends extra energy pumping a syrupy oil (this generates heat). Anecdotally, some 1KZ-TE owners find the engine runs quieter on a 15W-40 than a 10W-30 – this is likely due to the thicker oil dampening mechanical noise. But unless oil pressure was borderline with the thinner oil, the noise reduction doesn’t necessarily mean better protection; it might just be masking sound. Real protection is proven by measurements of wear (via tear-downs or oil analysis), not subjective impressions of engine smoothness.

Let’s bust a few myths along these lines in the next section.

Cutting Through Common Oil Myths (What the Evidence Says)

There’s plenty of lore in the automotive world about engine oils. Let’s address a few common myths, with a focus on older diesel engines, and see what tribology and testing evidence say:

Myth #1: “More ZDDP is always better for engine protection.”

Reality: Enough ZDDP is critical, but excess ZDDP can be counterproductive. ZDDP at normal treat levels (~0.1% P, ~1000 ppm Zn in modern diesel oils) forms an effective anti-wear film. However, piling in significantly more can lead to diminishing returns and even issues. For one, extremely high ZDDP can increase oil ash and leave deposits on valves and pistons. It can also conflict with other additives; for example, too much ZDDP can “crowd out” detergents and dispersants, reducing overall performance[47]. Research has shown that oil blends with moderate ZDDP (0.05% wt) plus balanced dispersant produced tribofilms just as protective as blends with much higher ZDDP[80][81] – indicating diminishing returns above a certain level. In fact, adding extra ZDDP beyond the balanced formulation can sometimes increase wear. How so? ZDDP’s film in excess can become too thick and brittle, flaking off under pressure and taking some metal with it – a phenomenon observed in some high-Zn racing oils. It can also promote camshaft spalling if not matched to the metallurgies. Additionally, ZDDP is a known poison for catalytic converters (its phosphorus fouls the catalyst), which is why API and OEM specs strictly cap phosphorus content for newer engines[82][83]. While your old 1KZ-TE likely doesn’t have a cat converter to worry about, dumping in extra ZDDP additive isn’t a magic bullet for longevity – it can upset the carefully balanced chemistry of a modern oil and potentially increase deposits or corrosion. Oil companies spend a lot of time determining the optimal ZDDP level for each formulation. As a rule, use an oil that meets the spec (which guarantees sufficient ZDDP for wear) and resist the urge to “spike” it with aftermarket Zn additives. More ≠ better beyond the engineered dose. And as we saw earlier, modern low-ZDDP oils have proven capable of protecting even flat-tappet cams by using alternative anti-wear chemistries (like molybdenum)[63]. In short, proper balance beats brute force when it comes to ZDDP.

Myth #2: “Synthetic oil is always the best choice (and must be used if you care about your engine).”

Reality: Synthetic oils (Group IV PAOs and Group V esters) do offer superior performance in extreme conditions – they flow in deep cold, resist breakdown in extreme heat, and can enable longer drain intervals due to higher oxidation stability[84][85]. However, “best” depends on application and value. For an older engine like the 1KZ-TE, which was originally designed around conventional oils, a high-quality Group II or II+ mineral oil can provide excellent protection under normal service intervals. The difference in wear between a synthetic and mineral of the same spec in moderate use is often negligible – because both must meet the same API wear tests[51]. Synthetics shine if you: frequently cold start in sub-zero temps, tow heavy in scorching heat, extend oil changes, or have a modern engine engineered for ultra-low viscosity. They also keep engines slightly cleaner due to lower volatility (less oil burn-off). But if your use-case is mild and you change oil at a reasonable interval, a premium mineral 15W-40 can run for hundreds of thousands of miles in a 1KZ-TE without issue. Cost and leak considerations: Older engines sometimes develop leaks when switched to synthetics – this is partly a myth (synthetic molecules are not significantly smaller to “seep” through gaskets), but it has some basis: synthetics can clean sludge that was plugging an existing weak seal, and their excellent flow can find pathways a thicker dino oil might not. If your 1KZ-TE has tired seals, a high-mileage mineral oil might actually reduce oil seepage due to slight swelling agents in those formulations. Maintenance is key: Changing your oil on time (and keeping the engine well-tuned) is more important than the base stock. A well-maintained engine on regular conventional oil will outlast a neglected engine on fancy synthetic. Indeed, extensive field data in fleets shows no difference in wear rates between synthetic and mineral as long as oils meet the spec and are changed appropriately[86]. Synthetics can be worth it if you need the extra temperature range – e.g. you want a 5W-40 for winter (most 5W-40s are synthetic or synthetic-blends) or you want to safely extend drains (with oil analysis monitoring). They are certainly “better” oils in technical terms – better VI, flash point, etc. – but they are not always necessary. For many 1KZ-TE owners, a quality 10W-30 or 15W-40 mineral diesel oil (API CH-4/CI-4) changed every 5,000 km will keep the engine alive just as well as a synthetic – and you can spend the savings on fuel or other maintenance. In essence, synthetic is best for hard service and cold climates; conventional is perfectly fine for average use and easier on the wallet[87][88]. Align your oil choice with how and where you drive. Both types are proven – remember, the 1KZ-TE came out in the 1990s when synthetic was not widely used, and those engines regularly last 300k+ km on proper conventional oils.

Myth #3: “Higher viscosity oils give more protection (thicker is better).”

Reality: This is a classic case of some is good, more is not always better. Yes, you need sufficient viscosity to maintain an oil film. But running an oil thicker than necessary can cause problems. If viscosity is too high for the engine’s temperature, the oil may not flow adequately, leading to poor lubrication on cold starts or in tight tolerance areas】[89]. Oil that is too thick can cause dry starts and starvation in parts of the engine until it warms up[89]. It also generates more heat from fluid friction and can reduce fuel economy and power. Engine bearings actually rely on a certain oil flow rate to carry away heat; overly thick oil flows slower, potentially keeping bearings hotter. There’s also the matter of the oil pressure relief valve – extremely high viscosity can just peg the pressure relief, meaning parts of the engine won’t see increased pressure beyond a point, they’ll just see reduced flow. The goal is to run the thinnest oil that maintains a strong hydrodynamic film under load – that gives you both good startup flow and protection. For most engines, that’s the OEM-specified grade. Going thicker may be justified in severe scenarios (e.g. continuous heavy towing in 40°C ambient – maybe bump from 5W-30 to 15W-40), but it’s not universally “better.” As a concrete example, Toyota’s manual for the 1KZ-TE explicitly states SAE 5W-30 is “the best choice... for good fuel economy and cold starting,” and it lists thicker grades only for higher ambient temperatures[50]. If thicker was inherently better, they wouldn’t prefer 5W-30. Tribology studies also show that lubrication regimes can shift if viscosity is too high – instead of a smooth hydrodynamic film, you get more turbulent flow or even starvation in areas, which can increase wear. An oil that’s too thick can’t be pulled into narrow bearing gaps quickly enough. This is why the OEMs have been trending to lower viscosities over the years (along with engine design changes): to reduce friction and ensure fast lubrication. To put numbers on it: at 0°C, a 15W-40 can have a viscosity over 1000 cSt, while a 5W-30 might be ~400 cSt – the 15W-40 is literally more than twice as thick in that cold start scenario. Those extra few hundred centistokes may mean your valvetrain isn’t fully lubed for several seconds longer, and those seconds count. In summary, use an oil that’s in the recommended viscosity range for your engine. Don’t assume a 20W-50 will make your diesel “last longer” – in fact, it might raise your oil temperature and increase engine wear at startup, negating any high-temp film strength benefits. Proper viscosity = proper protection. Too low = insufficient film; too high = poor circulation. The sweet spot is determined by engineering, and that’s what the SAE grade recommendations reflect. (As a side note, oil pressure is not a direct measure of protection – a very thick oil can show high pressure but low flow. It’s better to have the correct pressure with good flow at designed viscosity, than excessive pressure from overly thick oil.)

Myth #4: “All synthetic oils are the same” or conversely “Brand X is magic because it’s synthetic.”

Reality: Not all synthetics are equal – Group III, Group IV, and Group V base oils each have different properties, and the additive packages vary widely. One full-synthetic 5W-40 may focus on racing (high ZDDP, low detergents, not API licensed), while another 5W-40 synthetic is built for extended drains in emissions-equipped trucks (low SAPS, lots of dispersant, API CK-4). Their performance in your engine can differ. So don’t choose oil solely by “synthetic” vs “conventional” – consider the specific specifications and approvals. A high-spec conventional can outperform a low-grade “synthetic” in some tests. Always look for the API or ACEA category that meets your engine’s needs. And as mentioned, many synthetics use similar base stocks – it’s the formula that matters. Brand loyalty is fine, but base your choice on published specs and analysis, not hype. One owner’s UOA (used oil analysis) can tell you as much about their engine and duty cycle as about the oil – so gather broad evidence. The good news is, reputable brands and certified oils today (API CK-4, etc.) all undergo stringent testing. They have to pass ASTM engine tests for wear, deposits, viscosity control, foam, etc. If an oil meets API CK-4, for example, you can be confident it has passed tests like Sequence IV (valvetrain wear), MRV pumping, Mack T-12 (rings/liner wear and deposits), Cummins ISM (soot handling), and others [90]. In other words, trust standards over marketing. The best oil is one that consistently meets or exceeds the required standards for your engine and application – synthetic or not.

(We could go on with myths – e.g. “You can’t switch back from synthetic,” which is false; or “Always use the OEM oil brand,” which is unnecessary as long as spec is met – but the above are the major technical ones.)

Conclusion: Applying the Knowledge to Your 1KZ

For owners of older diesels like the Toyota 1KZ, cutting through the marketing hype means focusing on the fundamentals we’ve discussed:

Use a quality oil of the correct grade and specification. For a 1KZ-TE, that means an oil meeting at least API CF-4/CF (original spec) or preferably a newer API CH-4, CI-4, CJ-4 or CK-4 (each newer spec is backward-compatible and brings improved control of wear, deposits, and soot). Choose the viscosity grade appropriate for your climate: 5W-30 or 5W-40 if you experience cold starts in winter, 10W-40 or 15W-40 in moderate to hot climates (Toyota allows up to 20W-50 in very hot conditions)[78][79]. The manual’s preferred 5W-30 will cover most conditions and ensure easy starts and good economy[50]. Heavier isn’t automatically better – as we noted, it’s only called for in high ambient heat.

Appreciate what the additive package does – when comparing oils, look beyond vague terms like “synthetic” and see if the oil is marketed for diesel use or has the ACEA E7/E9, API Cx ratings. Those letters ensure it has the detergents, dispersants, and ZDDP levels for a diesel. For example, some 5W-30s are made for passenger cars (API SP, minimal ZDDP and detergents) – not ideal for an older diesel. On the other hand, a 5W-30 heavy-duty diesel oil (API CK-4/SN) will have the needed additives. It’s the additives that make a diesel oil “diesel.” If you run your 1KZ-TE on a heavy-duty 15W-40 (e.g. Shell Rotella, Chevron Delo, Mobil Delvac), you’re giving it high TBN to neutralize soot acids and plenty of dispersant to handle soot, as those oils are designed for trucking service.

Base oil choice (conventional vs synthetic) should align with your use. If you frequently see sub-zero cold starts or extended high-load running (long highway trips, towing in heat), a synthetic 5W-40 or 0W-40 will flow better and resist breakdown – potentially extending your turbo’s life by getting oil to it faster on cold starts and coking less. If your usage is mild and you change oil every 5,000 km, a conventional 15W-40 will likely keep your engine just as wear-free. Many 1KZ-TE drivers report excellent longevity on conventional oil – these engines aren’t extremely hard on oil (no unit injectors, no DPF constraints). Just avoid extremely long intervals on conventional oil, as its oxidation stability is lower.

Real-world testing and data trump marketing. The principles of tribology (friction, wear, lubrication science) that we’ve referenced show that properly formulated oils prevent wear under a wide range of conditions. Whether an oil is labeled “diesel ultra protection” or “Euro blend” matters less than the actual test results it achieves. Look for API and ACEA sequences and even OEM approvals (like MB 228.3, etc.) if you want an extra layer of assurance. Those are hard to get and indicate the oil was proven in tough engine tests. Marketing claims like “nano-particles” or “racing formula” might not translate to better protection in your engine (sometimes those skip detergent for short-term performance, which you don’t want in a daily diesel). So be a healthy skeptic: rely on standards, oil analysis, and reputable sources. A good CJ-4/CK-4 oil will have performance confirmed by millions of miles of fleet testing[91] – that’s more meaningful than any one anecdote.

Don’t fall for “magic additive in a bottle” solutions. Additives like aftermarket ZDDP boosters, PTFE treatments, etc., are generally unnecessary or even harmful when you’re already using a well-formulated oil. As we discussed, more ZDDP can upset the balance and plain diesel fuel already provides lubrication for injectors, etc., so you usually don’t need to spike your oil or fuel with extra stuff unless addressing a known deficiency.

Monitor your engine’s needs as it ages. A high-mileage 1KZ-TE with some wear might benefit from slightly thicker oil if oil pressure at hot idle is dropping – but that’s a case-by-case tuning (and typically 15W-40 instead of 10W-30, for example). Conversely, if you rebuilt the engine tight, you might run a 5W-30 in winter for easier cranking. Use oil analysis if you’re curious – it can reveal if your oil is shearing or if soot is too high, etc., which can guide adjustments in oil choice or interval.

In essence, the best oil for your diesel is one that meets the right specs, in the right grade, changed at the right interval for your usage. Understanding what’s inside that oil – the groups of base stocks and the medley of additives – helps demystify why that oil works and why some claims are snake oil. There’s no single “super oil” that’s light years ahead of others if they all meet the same certifications; there’s a level of performance each spec assures. As consumers and enthusiasts, knowing the technical backbone (like how ZDDP actually forms protective films, or how Group II+ base oil is clear as water and why that matters for oxidation) empowers us to make informed decisions and not overpay for something that doesn’t actually benefit our engine.

Finally, always remember the real-world evidence: Engines like the 1KZ-TE have been in service globally for decades. Those running on appropriate oils (even mineral oils) and proper maintenance have lasted hundreds of thousands of kilometers. Tribological research and standardized tests give us confidence that we don’t have to guess – we can rely on measured performance. So whether you’re a daily driver or an off-road adventurer in a Hilux Surf with a 1KZ-TE, you can feel secure that if you feed your engine a quality diesel oil and keep it topped up, the machine will reward you with a long, healthy service life. No myth or marketing required – just good oil based on good science.

References: The information above was drawn from tribology research papers, industry publications, and standards documentation – including API definitions of base oil groups[5][16], Shell’s technical explanations of diesel additives[27][30], comparative studies on ZDDP and dispersants in wear testing[80], and manufacturer data like Toyota’s own oil recommendations for the 1KZ-TE[50]. Real examples such as the viscosity curves[71] and test results from Infineum’s heavy-duty trials[45] were used to illustrate key points. All sources confirm the overarching theme: lubricant performance comes from a well-balanced formulation of suitable base oils and a purpose-built additive package, proven by rigorous testing – the rest is mostly branding. Use that knowledge to maintain your diesel engine with confidence! [5][50]

[1] [6] [22] [23] Base oil basics: Quality starts at the base | Chevron Lubricants (US)

[2] [25] [26] [27] [30] [41] [42] [43] [46] [91] How Diesel Oil Additives Work? | Shell Rotella®

https://rotella.shell.com/en_us/info-hub/how-oil-additives-work.html

[3] [4] [5] [7] [8] [9] [10] [11] [12] [13] [14] [15] [16] [17] [18] [19] [20] [21] [24] Base Oil Groups Explained | Machinery Lubrication

https://www.machinerylubrication.com/Read/29113/base-oil-groups

[28] [39] [47] [80] [81] Wear Mechanisms, Composition and Thickness of Antiwear Tribofilms Formed from Multi-Component Lubricants - PMC

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11122858/

[29] [31] [32] [33] [34] [35] [36] [37] [38] [40] [48] [49] [53] [54] [55] [56] [90] Gasoline vs Diesel Additives Explained | Top Polymers

https://www.toppolymers.com/gasoline-vs-diesel-additives-key-differences-explained/

[44] [45] [72] [75] Infineum Insight | Next generation viscosity modifiers

https://www.infineuminsight.com/en-gb/articles/next-generation-viscosity-modifiers/

[50] [78] [79] toyotamanuals.gitlab.io

https://toyotamanuals.gitlab.io/PZ471-Z00W0-CA/htmlweb/rm/rm990e/m_17_0027.pdf

[51] [52] [57] [63] [82] [83] High levels of ZDDP can actually cause wear. The ZDDP under heat/pressure reacts...

https://pedrosboard.com/read.php?7,30533,30536

[58] ATF vs ENGINE OIL | BobIsTheOilGuy

https://bobistheoilguy.com/forums/threads/atf-vs-engine-oil.77361/

[59] [60] [61] [62] Gears Magazine - The One, Two, Threes of ATFs, Part I

https://gearsmagazine.com/magazine/the-one-two-threes-of-atfs-part-i/

[64] [65] [66] [67] [68] Engine Oil Viscosity Explained | SAE J300 Chart

[69] [70] [89] Viscosity Index Explained: Why It Matters More Than You Think - Fubex

https://fubex.net/blog/viscosity-index-explained-why-it-matters-more-than-you-think/

[71] Motor oil graphs | Widman International SRL

https://www.widman.biz/English/Tables/gr-motores.html

[73] [74] [76] [77] Oil Viscosity | Blackstone Laboratories

https://www.blackstone-labs.com/oil-viscosity/

[84] [85] [87] [88] Choosing Synthetic vs. Mineral Oil in Industrial Applications - AMSOIL Industrial Blog

[86] Test Of Bearing And Oil Wear Rates - Conventional vs Synthetic